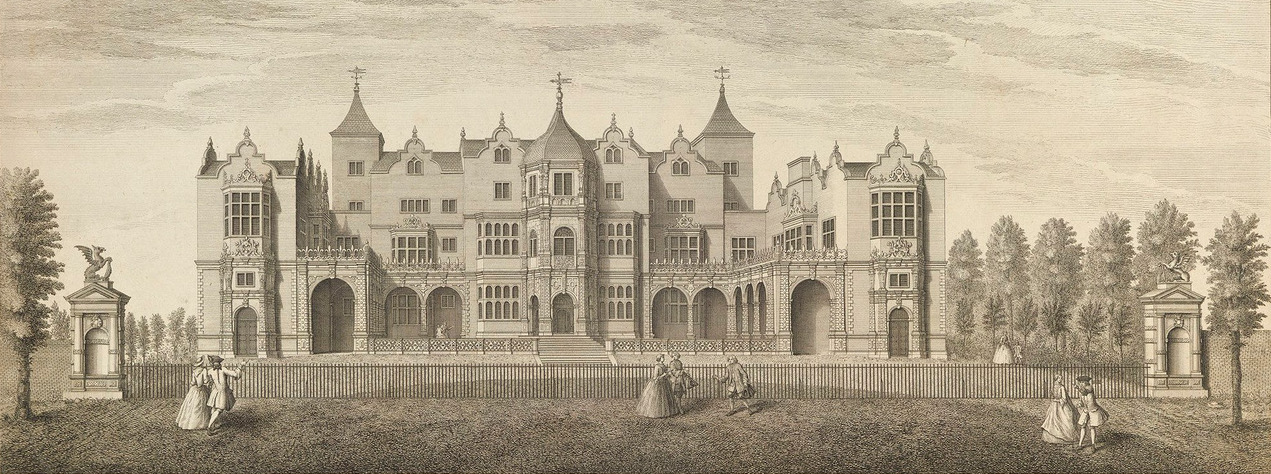

Holland House, Kensington, was one of the most important cultural sites in late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century London. The circle established there was known across the continent, and the portraits of Renaissance Europeans that adorned the walls of the house helped set the stage for a cosmopolitan group that advocated reform in Britain and Europe. The coterie kept alive the flame of Charles James Fox, the uncle of Henry Richard Vassall-Fox (Lord Holland), and continued Fox’s fight for the emancipation of enslaved people, his opposition to European wars, and his support of global freedom movements. The international dimension of these concerns meant the house was a kind of alternative foreign office for liberal culture and politics, receiving European authors and politicians who it was hoped would spread Foxite principles abroad. The centre of exchange for this group was the dining room, in which Elizabeth Vassall-Fox (Lady Holland) played chatelaine, entertaining the leading cultural figures of the day.

Lady Holland’s assiduously kept dinner books document forty five years of the salon. The dinner books operate a uniform recording system: diners are listed in no apparent order before dinner takes place and those who failed to attend are deleted the following day. Those who slept the night are marked as ‘slept’ or with an asterisk (and are marked on the Dined database by an “(s)”).

Elizabeth Vassall Webster met Henry Richard Fox, Lord Holland, in Italy in 1794. They began a friendship that became an illicit courtship which continued at the departure of Elizabeth’s husband (Sir Godfrey Webster) in 1795. The two spent much of the period 1794 to 1796 together in Florence and conceived a child (Charles Richard Fox) there in early 1796. The Hollands studied Florentine society to an unprecedented degree. They befriended the Countess of Albany, widow of the Young Pretender, who was both the city’s most important saloniere and the lover of Italy’s foremost living author, Vittorio Alfieri. Inspired by the countess, Lady Holland created her own salon on the via Mattonaia in winter 1795, which dined three times a week and included among its intimates Felice Fontana (polymath and professor at Pisa), Angelo Fabroni (Renaissance historian), Melchiorre Delfico (economist and philosopher), Ottaviano Targioni Tozzetti (botanist), and the celebrated French artists Louis Gauffier and François-Xavier Fabre. In 1797 they returned to London: Elizabeth sought a divorce, and, two days after it was granted, she married Lord Holland and became Lady Holland. As Lady Holland’s Journal (see Further Reading) attests, in 1798 they began hosting dinners at their newly-decorated home for many of the leading figures of the age. Lady Holland began to keep note of attendees, a process which she moved to dinner books in 1799 and would perform for the next forty years.

The Dined project has created a database of the first dinner book (British Library Add MS 51950) which covers the period May 1799 to April 1806. The book also records many of the great events of these years including the battle of Trafalgar and the Acts of Union with Ireland, and the death of national figures such as the Duke of Bedford, Nelson, and Pitt the Younger. In the republic of letters, attendees at Holland House published major works such as Thomas Campbell’s celebrated The Pleasures of Hope (1799); George Ellis’s ground-breaking Specimens of Early English Metrical Romances (1805); Etienne Dumont’s Traités de législation civile et pénale (1802) which spread Benthamite ideas to the continent; the economist Lord King’s Thoughts on the Restriction of Payments (1803); and, in philosophy, Uvedale Price’s Dialogue on the Distinct Characters of the Picturesque and the Beautiful (1801). Perhaps more important than all of these was the founding of the Edinburgh Review in 1802—arguably the most significant periodical of the nineteenth century—with three of its founding members (Henry Brougham, Francis Horner, Sydney Smith) dining at the House in this period. The Hollands were committed to travel, and they had learnt their mode of sociability abroad. The dinner book shows their extensive travel in this period with trips around Britain, a summer in France during the Peace of Amiens, and a tour of the Iberian Peninsula. When based at home in Kensington the Hollands regularly attended the theatre in town, and Lord Holland was a quite assiduous attender of parliamentary debate (this political activity culminates in his entry into the Ministry of All the Talents in 1806).

The Search function allows you to look through the dinner book by date and person, while you can simply look at images of the manuscript itself using the Browse function. You can see the biographical information on those who came to dinner at Holland House in the Index of People. These books also act as something of a coterie diary, noting when the Hollands and some of their party dined elsewhere or went to the theatre, and marking holidays to the country or longer trips abroad. You can see the places visited by the Hollands by browsing the Index of Places, and what they did in the Index of Events. The indexes can also be searched and compared using a three-digit code system with people referred to as peXXX (e.g. Lady Holland is pe001); places as plXXX (e.g. the House of Lords is pl003); and events as evXXX (e.g. a play is ev002).

An open-access scholarly article with an analysis of this dinner book and consideration of the utility of this medium for the study of sociability is currently in progress.